Earlier this year I was wandering down the main street of Callander near Stirling in Scotland when one of the shop windows brought me to a sudden halt. If you’ve visited the ‘Loch Lomond and the Trossachs’ area or the Highlands, you’ve probably done a pit stop there for coffee and the loo before returning to Glasgow or onwards to slog down the M74 south. It’s a very pleasant small town, but apart from an excellent bakery most of the shops cater for hikers, ramblers or American tourists in search of assorted woollen goods. So as a lover of bright sparkly things I was caught unawares by this window of exquisitely beautiful and unusual jewellery.

So why did a very satisfying bit of upmarket souvenir buying provoke me into writing this piece? Every craft fair and craft centre the length and breadth of the country is packed with people who claim that their work is influenced by the natural environment. This usually means that there are a few herbaceous motifs scattered across the earrings and the brooches have wiggly lines or a few feathers attached. It is rare to find artist designers who truly embody and express their rootedness in a particular locality.

In other expressions of creativity this is more common and in contemporary folk music almost a prerequisite. Over the last twenty years some folk musicians have become virtual ambassadors for their home region, the Lakemans in Dartmoor, Kate Rusby in Yorkshire, the Unthanks in Northumberland and more recently Ninebarrow in Dorset. In some ways it is easier for musicians, painters and writers. There is often a rich heritage to draw upon, both actual artefacts (books, paintings, sheets of music) and the history of human interaction with a locality’s landscape through local traditions and customs. So, there is plenty of material to interpret and react to as well as in the actual geographical environment. For artists who are jewellers producing work generated by their relationship to a particular locality it is further complicated by the very nature of the artefacts they are producing. Their work needs to attract me enough not only for me to look at it but also to own it and wear it.

It is not an accident that some pieces of jewellery attract our attention more than others. The artist has made a series of design choices and must be in command of a vocabulary of design elements that they are able to bring together into a coherent whole. They must also have a high level of technical skill in their chosen medium to translate their design into a high-quality artefact. That level of design and technical competence must be there if an artist is then going to be able to channel something so esoteric as ‘rootedness in a landscape’ convincingly into their work.

So how does all of that relate to me stopping dead in my tracks outside Heather McDermott’s shop in Callander? What feels like an age ago back in the early 1980s I did a post graduate diploma in art and design history; it seemed like a great idea at the time and it was in the sense that I discovered that I really wasn’t that suited to the academic life. What it did give me with was a good understanding of what good design looks like and an appreciation of when an artist has transcended technical competence and is producing something special.

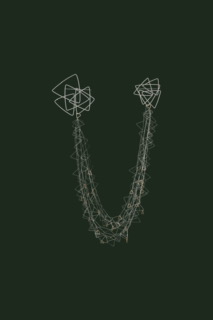

Heather McDermott is a goldsmith and silversmith, she describes herself as specialising in contemporary jewellery and she takes her inspiration from the shoreline of her childhood home on the Isle of Skye, where she grew up. I have had a couple of conversations with Helen, in the shop during our visit to Callander and later on the phone after I’d decided to write this piece. What struck me on both occasions was the deep and genuine connection that she has to the natural environment she grew up in and how it influences every aspect of her artistic practice in precious metals. She incorporates the human impact on that landscape into her work so that the flotsam and jetsam on the beach, and the more industrial artefacts like bits of stainless steel, fishing nets, lobster pots and buoys all make their mark.

She says on her website that the inspirational scenes of Skye’s tide lines “are developed and translated in my work by utilising shapes and colours. Unconventional in size and structure, each piece is an expression of sculptural form and is designed to create a statement.”

Heather has been making jewellery and other decorative artefacts since she was very young and I got the impression that her formal training at Edinburgh College of Art (BA MA in Jewellery) provided her with a technical and intellectual underpinning for what was and already well-developed aesthetic.

The other artist I want to look at arrived at a similar place, though by a different path. Lucy Campbell is a goldsmith and silversmith based in Lyme Regis in Dorset. Lucy grew up on a quite different stretch of coastline to the Hebrides. Lyme is defined in our memories by the safe harbour provided by its iconic Cobb, the site of Louisa Musgrave’s plot altering fall in ‘Persuasion’ and the dramatic look out spot for ‘the French Lieutenant’s Woman.’ However, there is also a wild side to this part of west Dorset, part of the world heritage Jurassic Coast site. The surrounding cliffs are prone to collapse making them incredibly attractive to fossil hunters.

It is this aspect of her locality to which Lucy is drawn creatively, the rock pools, the fossils and the beaches. She says on her website “I try to capture patterns, textures and forms from the beach and translate these into metal; primarily in silver but also in gold too” she went on to say in conversation “ I use fossils in my jewellery but the use of them and the influence behind my own work is also related to childhood memories of collecting pebbles, fossils and other ‘treasure’ on the beach. I like the idea that people can trigger their own seaside memories through my work”.

Lucy took some time to come to her way of working and it was during her training on Camberwell’s BA in Silversmithing and Jewellery that a chance guest lecture by someone in a very different field opened a door into a new way of working. Annie Turner is a ceramicist who lives and works on the Debden estuary in Suffolk, a very different coastline however like the Jurassic coast it is rich in fossils, she and Lucy have a shared childhood love of collecting them in common. Annie’s ceramic pieces are extraordinary responses to the colours textures and history of her river and coastline. By chance I saw Annie’s work in a Cavaliero Finn exhibition a few years ago and they are breathtakingly beautiful. One of Lucy’s tutors at Camberwell School of Art recognised that she would inevitably be drawn back to the coast when they noted that the sea was ever present in her work. The encounter with Annie showed her how she could integrate her technical knowledge with her visual and emotional influences drawn from the Dorset coastline evolve her own artistic process.

I appreciate artists across many disciplines whose work comes out of a particular landscape and experiencing their landscape through their work gives me a great deal of pleasure and a vicarious insight into someone else’s world and personal history. These artists evoke memories of their landscapes, not just how it appears visually but elements of remembered emotion. They have all retained their childhood joy of collecting the found items on the beach whether shells, fossils or bits of fishing net. Through the complex technical demands of their craft, they are able to draw upon their past to create personally authentic work in the present.

Clearly there are other wonderful artist designers out there who are similarly rooted in a locality and producing complex, interesting work. So please do mention them in the comment, I would love to hear about them.

How interesting and thought-provoking it is to read about the glitter of jewelry celebrating the memory of distant the locality of the Devon shoreline. The blog is a tale of surprising discovery: a drive, a jaunt to a town, a peek into the window, arresting artefact, the story of the local artist in conversation with the Devon landscape and her memory… It’s a little more complicated in Toronto, Canada where I live because the land I/we/settlers live on is occupied indigenous land. A shoreline is not just a shoreline, not a simple “her river” of fond personal memory but a river that was once traversed by people over thousands of years before we, the colonists arrived. Rivers, lakes, forests, were honored by complex indigenous mythmaking and tradition: a few years ago I was awed by an indigenous woman in full regalia beating and drum and singing to the Humber River as I kayaked by. Today in Canada as part of Reconciliation process and “making right” with tribes subjected to genocide, we are asked to consider the ways of the peoples who lived by various shorelines, travelled following rivers, told tales of various landscapes. In the case of Tkaronto the land acknowledgement reminds us that “Toronto is located on the traditional territory of the Wendat, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and the Anishinaabeg, including the Chippewas and the Mississaugas of the Credit.” Those two memories, our personal memory of any landscape here and the cultural memory of these tribes, indigenous people’s approach to land/scape layers my understanding of “locality”.

I admit, I did not do a road trip. I did a simple and perhaps sloppy, but rewarding google search (No AI!). I present to you the Sapling and Flint collections which speak the cultural memory of the Haudenosaunee and Mohawk people. For instance: https://www.saplingandflint.ca/collections/karhakon. Karha: kon means “In the Woods” and represents the mission of the artefacts: ” At Sapling & Flint, our designs are conversation pieces that share the story of Turtle Island”. In other words, each piece of jewelry signals a story that goes beyond personal taste and opens up a world almost lost to our greed and grandiosity. If I were to buy any one of these items, I would owe it to the art and artists that I consider the history that has beaten it into its glorious and numinous shape.

Personal favorite: https://www.saplingandflint.ca/collections/leaders-of-the-four-legged–check out the deer!

Really interesting observations Eva. Our relationship to the land is complex when that land has been colonised. The Sapling and Flint collections are beautiful and speak of history of a people as well as an individual’s personal memory. Thank you for such a rich and thoughtful response.

Maureen’s piece and Eva’s response reveal just how landscape is plumbed into our psyches – our emotional ballast. I’m also starting to bring landscape into my work and these young women jewellery makers have referenced it at an impressively young age. I’m getting on a bit and am thinking and feeling fondly back to the Surrey countryside of my childhood. Although farmed and ranged by the rich – it was us working class kids who climbed the trees and picked the blackberries – and primroses, and chestnuts, conkers, violets and bluebells and scrumped the apples . This bucolic image isn’t quite right; we got scratched, yelled at and stained. We needed to be in packs or pairs. It was walking alone through woods and across fields that the maternal beauty of it all took hold. I did a fair bit of horse riding alone too . Quite often a rich kid was bought a pony and gave up on it. So yours truly was around to offer to help exercise, feed and muck out. Half a crown for my trouble too. There’s a difference between country side and landscape. The beauty of the jewellery that Maureen describes and wears would be merely pretty if it were dangling blackberry earrings or flowery necklaces; it’s the sweep and shape of hills and coast that makes it special. Landscape is personal and collective at the same time; my place and our place. I’m working towards an exhibition ‘Landscape Framed’ (current title) of paintings at the Tavistock Gallery London this December. It won’t be nostalgic but a way of looking at landscape through various media and with a political edge. Maybe one or two will be beautiful, like Maureen’s jewellery.

Thanks Jan, ‘emotional ballast’ is a great description.