“The Zone of Interest” is a remarkable movie. It is also, in the most profound sense, a deeply disturbing piece of work. After all, the definition of “disturb” includes, ‘to stir up, trouble, disquiet’, ‘to unsettle’, ‘to discompose the peace of mind’, and many other similar terms.

Why is this? After all, there have been many filmic attempts to come to terms with the Holocaust. As early as 1945 Sidney Bernstein worked with Richard Crossman and Alfred Hitchcock on a documentary detailing the atrocities at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp. The footage served as evidence at the Nuremburg trials, but was considered too graphic for general release until Andre Singer edited the material for the 2014 film “Night will fall”. From the documentary form of Alain Resnais’s 1955 “Night and Fog” and Claude Lanzmann’s mammoth 1985 “Shoah”, to Steven Spielberg’s Hollywood 1993 “Schindler’s List”, and many other examples, film-makers have tried in different ways to answer the second of the historian’s tasks: to explain why it happened.

Since Hannah Arendt reported on the trial of Adolf Eichmann the “banality of evil” has become a much-employed method of coming to terms with the awfulness. Arendt had travelled to Jerusalem for the trial, expecting to see a monster in the dock. What she saw was much more unsettling, because she saw instead a rather dull bureaucrat whose solutions to mass murder were akin to the logistics of manufacturing ball bearings.

“The Zone of Interest” positions itself alongside that approach. There are no atrocities on display, yet they are ever-present. The film achieves this by constantly underpinning what we do see on screen with implications that freight each moment. As the film’s narrative is almost irrelevant it seems reasonable to discuss some examples.

A pile of clothing is placed on a table, for the servants to choose ‘just one item’. A fur coat, rather too large, is tried on and a lipstick is found in the pocket. The origins of the items are not made explicit and so the evil of banality (and I do want to reverse the terms) is a matter we have to unravel for ourselves. ‘Normal’ activities are contextualised in a way that makes them deeply troubling.

A small boy watches out of a window an event to which we have no access, though it is presumably the drowning of two camp prisoners. He watches and then returns to playing with his toy soldiers, saying “don’t do that again”. Yet we do not know what he means: is this a warning to other prisoners, an appeal to the killers, or an instruction to himself? Each is possible.

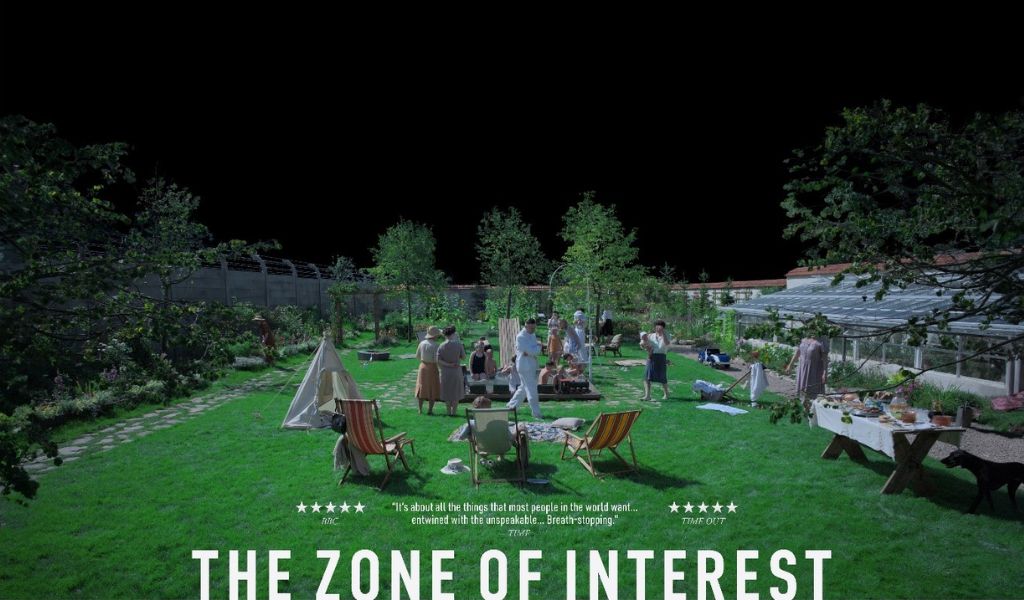

In a film that lacks drama in a conventional sense the dramatic climax of the film, for me, is the argument between Rudolf and Hedwig Höss, when he is ‘promoted’ from commandant of Auschwitz to overseeing the whole programme of mass slaughter. Because Hedwig’s outrage is directed towards the loss of her garden, which she has cultivated with care for two years, wreathing the wall between the garden and the concentration camp with vines and roses. The disparity between what she feels at this moment and what we would like to believe would be our own outrage at the crimes being committed on the other side of the wall is shocking precisely for its absence from the film itself.

Hedwig’s ‘blindness’ to the situation is mirrored, beyond the confines of the film, by Rudolf’s farewell letter to her written very shortly before his execution after conviction at Nuremburg:

Based on my present knowledge I can see today clearly, severely and bitterly for me, that the entire ideology about the world in which I believed so firmly and unswervingly was based on completely wrong premises and had to absolutely collapse one day. And so my actions in the service of this ideology were completely wrong, even though I faithfully believed the idea was correct.

The question the film poses in response to this letter is, ‘why was this not obvious to you AT THE TIME?’

The answer that the film seems to offer within itself, is that the everyday business of everyday life, including children, servants, a garden, birthday parties, going to work, keeping the house tidy, can disguise the atrocities beyond – no matter how close they might actually be.

The film achieves this by juxtaposing a close visual surface of everyday activity that for much of the film excludes anything beyond the house and garden, with off-camera sounds and noises that we attempt either to push away even as they intrude, or to which we attend as a counterpoint to the blandness of what we are watching.

This is a remarkable commentary on the larger and more difficult question; how we respond to the atrocities and crimes of the world we inhabit beyond the cinema.

Thanks for a great review of a singularly and chillingly “bland” movie on the “banal.” The striking feature is as you point out, the element of “disguise” and in that I am struck how, for lack of better words, intellectually subtle? elitist? the movie is. I don’t like the word “elitist” but can’t think of a better word to reflect on how the movie divides viewers in the “know” from those who have no idea about a KZ.

Missing any exposition, the weight of understanding of the implications of each gesture, movement, sound, falls entirely on the informed (or uninformed?) viewer. And if the viewer cannot see past the aesthetic “disguise” of cinematic restraint, it’s practically a boring family movie about a mysterious job and a garden. You have to know about the “mass slaughter” to generate the contextual horror. And deduce that the job of the rose is to disguise the smell of the job, but what is the job, actually? How well do we have to know the history of the lager to appreciate the “Canada” reference? What other references are we “blind” to just the Hoss family remains necessarily blind to the job that sustains the family? That is the shape of the banal: a singularly circumscribed vision.

The final question of your review, spot on: “How we respond to the atrocities and crimes of the world we inhabit beyond the cinema.” It depends how much we want to be informed and how much knowledge we can bear.

IMHO to grasp the enormity of the horror Zone would be best shown with Night and Fog, if only to counterpoint the daily realism of camp experience with the cinematic distance of the chronicling of the banality of evil.