Over the last year, I have written about three hundred sonnets. The constraints of the form, fourteen lines written in iambic pentameter with a regular rhyme scheme, present a challenge for the poet. One must learn to express his/her deepest feelings with clarity and precision while the floodgates of the heart are open. This is not an easy task, but nothing is easy in art.

I find comfort in knowing that I am not the first poet, nor the last, to struggle with this challenge. The earliest evidence of the sonnet comes to us from the hand of a 13th century Italian poet by the name of Giacomo da Lentini, who used it as a vehicle to express courtly love. Sir Thomas Wyatt is credited with bringing the sonnet to England through his translations of Petrarch. The form was used by almost all of our most notable poets, from Sidney to Spencer to Shakespeare to Donne. After Milton the form declined in popularity, but it was revitalised by the Romantics, probably due to the rising tide of female poets in the 18th century who were seeking to establish themselves within the English literary tradition. The first collection of sonnets to be published by a female writer was Elegiac Sonnets by Charlotte Smith, in 1784.

Much can be said about the rise and fall in popularity of the sonnet since then, and the reasons why this occurred. What matters even more is not the changing popularity of the form, or its varying subject matter, but its enduring legacy. The sonnet has long been an apprentice form – a form that poets learned to master before they could move on to experimenting with larger, more complex forms, like the epic.

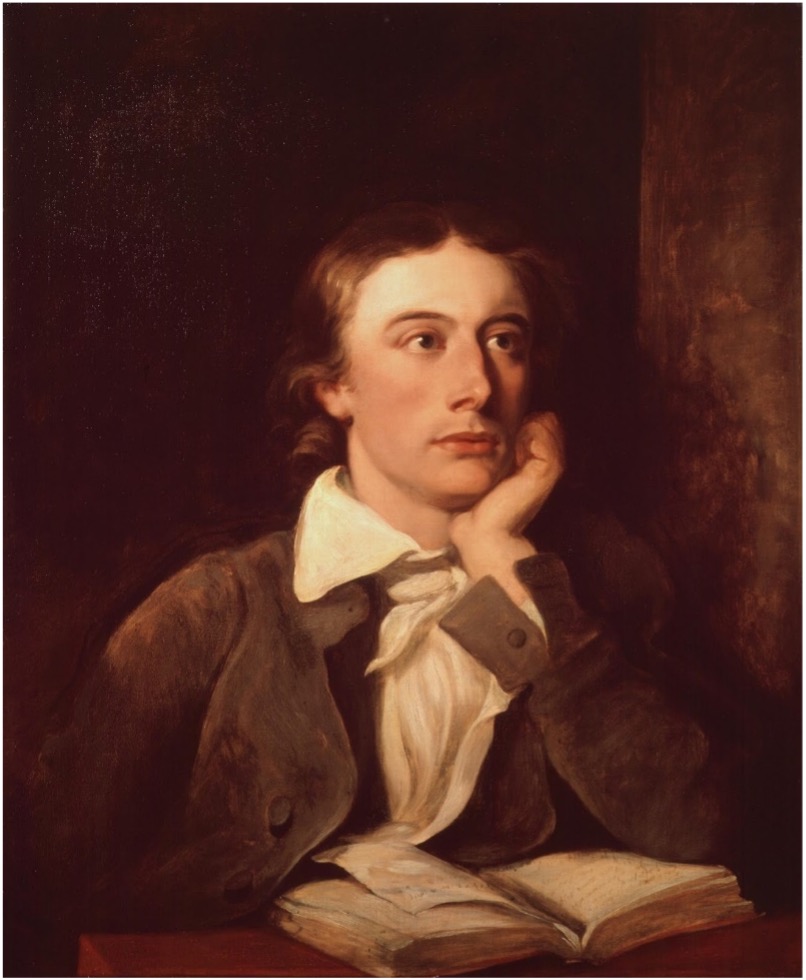

Just as a traditional sculptor might spend years practicing on smaller head busts before moving on to more elaborate shapes and figures, so a poet would learn their craft in a traditional way by writing sonnets, honing the use of metaphor and simile, the ability to write in metre and rhyme, learning to think in images and mould the language into its desired shape. The number of sonnets available to us today from different historical periods allows us to connect with the past in a very intimate way. I feel this is beautifully captured in the following sonnet by John Keats, who devoted his tragically short life to the perfection of his poetry, and believed, probably more ardently than any other poet, in the healing power of sensuous language and imagery.

How many bards gild the lapses of time!

A few of them have ever been the food

Of my delighted fancy,—I could brood

Over their beauties, earthly, or sublime:

And often, when I sit me down to rhyme,

These will in throngs before my mind intrude:

But no confusion, no disturbance rude

Do they occasion; ’tis a pleasing chime.

So the unnumbered sounds that evening store;

The songs of birds—the whispering of the leaves—

The voice of waters—the great bell that heaves

With solemn sound,—and thousand others more,

That distance of recognizance bereaves,

Makes pleasing music, and not wild uproar.

Just as Keats heard the “pleasing chime” of earlier poets, now I hear the delicate voice of his poetry when I write, and I feel in some sort of spiritual communion with him and all other poets that, as he put so beautifully, “guild the lapses of time”.

This goes to show how poetry can transcend those who produce it – it derives its power from this transcendental quality, which can only be achieved through the meticulous challenge of self-expression.

Anybody can write in iambic pentameter with a bit of practice, but matching words to the rhythm of da dum da dum da dum da dum da dum is not necessarily poetry (eg. the moon was glowing in the starry night). Poetry must be written from the heart, which means that it must give shape to the nebulous shadow of the soul from whence it came. In other words, it must somehow reflect an individual way of seeing or experiencing the world which is unmistakeably unique.

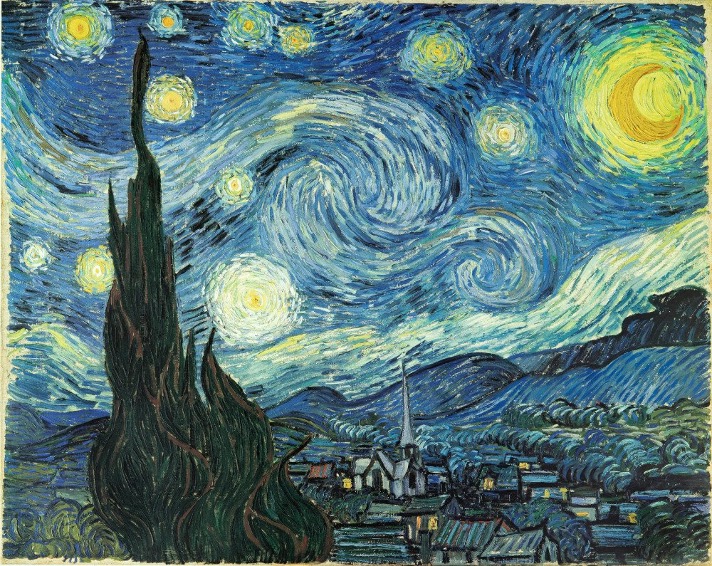

Anybody can see the moon glowing on a starry night, but only one person could see it in the way that, for instance, Van Gogh saw it from the east-facing window of his asylum just before sunrise in 1889:

Thankfully, poetry is a craft that requires very few tools. All that is needed is a paper and a pen, but even a napkin and a pencil will do fine. A rhyming dictionary can help in the beginning, but one should be careful not to rely on it too much, because doing so would prevent them from acquiring the skills that make rhyming second nature. A thesaurus can help too: there are estimated to be about one million words in the English language, and one cannot possibly know them all. Finding a new word can help to express something more clearly, more concisely, or perhaps more rhythmically.

As with an any craft, it requires dedication and discipline to master. In addition, writing is usually a solitary activity that requires sitting down for long periods of time while being hunched over a desk, so the best advice that I can give for any budding poets like myself out there who may be reading this is to remember that it is important to have some contact with other people and do some exercise now and again.

Some days it can be difficult to get started, and even more difficult to keep going, but there are ways to overcome this. If you are still reading this, you may have gathered that I am a fan of John Keats, and that I hold him in the highest regard as a poet. While writing his first epic poem, Endymion, in order to get started on days when he did not feel motivated, he would dress himself in his finest outfit, as though he were about to go into town. He would open the front door and then immediately run back to his desk and start writing. Indeed, he is a guiding light to us all. There is, however, a danger to approaching poetry solely as a craft or as a technical skill. In my experience, forcing myself to write all those sonnets did not help me to produce any real poetry, but it did help me to feel more adept at using the form so that when the inspiration really does come, it flows more easily into shape. There is a vital element missing to the sole practice of poetry as a craft, and that is the element of mystery. This, I believe, can only be achieved through a relationship with divinity, whatever that word means to the poet. It requires complete faith in the creative powers of the soul. There can be no holding back. To write poetry, in its most essential form, is to worship at the shrine of beauty, and only those who believe in its existence are permitted to enter.

Enjoyable and profound. A fine piece from a young poet. Like all art foms it has to come from the heart – art from the heart – but there is discipline too – as in disciple.