Of course I knew Mary Wollstonecraft. I had a copy of A Vindication of the Rights of Women I bought decades ago. I must have read it but so long ago I couldn’t really remember anything about her at all. Then Maggi Hambling’s statue appeared in London’s Newington Green, near where Wollstonecraft had briefly run a school. You could say that the statue divided opinion. Was a naked woman appropriate to commemorate a feminist in this sexist age? Why not a ‘realistic’ portrayal of the ‘Mother of Feminism’? So off I went, my partner in tow, to inspect the statue for myself.

‘Mary Wollstonecraft’ emerges, borne aloft by a mass of limbs, a fitting image of the 1789 French Revolution that impacted her life. Revolutions shape not only the lives of the direct participants but send ripples far and wide. In my case, campaigning for the victory of the Vietcong followed by the general strike in France in 1968 changed my understanding of society, how it worked and how it could be so different. It changed what was important to me, what I did – right down to how I dressed.

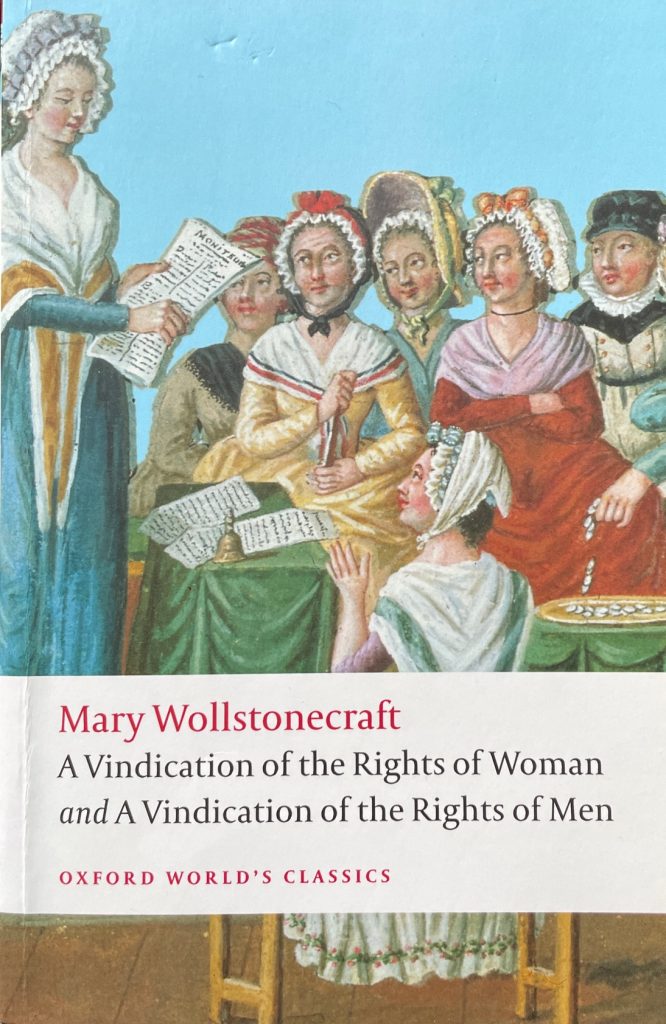

The French Revolution transformed Mary Wollstonecraft, from a reviewer and translator for Joseph Johnson’s Analytical Review, into a public intellectual. She wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Men, the first reply to Edmund Burke’s attack on the French Revolution – before Tom Paine’s better known The Rights of Man. A Vindication of the Rights of Women, the book most associated with her name today, followed in 1792.

But how did she even get to work for the Radical publisher Joseph Johnson? And how did he become one of her staunchest supporters? People aren’t just ciphers for social forces. There is a complex interaction between individuals and the social spaces they occupy, why they occupy one space and not another. Her father’s fortune lost through alcoholism taught Wollstonecraft that individual choices made a difference.

Mary Wollstonecraft was born not far from where I live now in the East End of London into a family that should have been comfortably off. Instead, they ended up poor. Wollstonecraft drew three conclusions from her childhood during which an indifferent mother and a drunken, violent father dragged her and her siblings from farm to farm and into ever-increasing poverty. She determined to be independent and escape the fate of being a dependent and subordinate wife, the usual fate for middle class women. She decided girls should be educated to as high a level as boys and not just trained to be empty headed, physically weak sex objects in marriage. And girls as well as boys needed to experience physical activity outdoors, as she herself had done and I did too growing up in the Lake District.

Her first stabs at independent living were in various postings as a governess. She appeared to have related well to the children in her charge but loathed both her socially inferior status and the false manners of the gentry. Fortuitously, an experiment she undertook to run a school with her two sisters Everina and Eliza, and her close friend Fanny Blood, took her to Newington Green. This brought her into the circle of the Radical Dissenters, in particular one Dr Richard Price whose sermon on November 4th, 1789, in support of the French Revolution, provoked the wrath of Edmund Burke.

Wollstonecraft had already absorbed as much as she could from her close friend Fanny Blood, whose writing skills she had admired. Now she encountered radical publisher, Joseph Johnson, who convinced her she could live by writing and took her on at the Analytical Review, a publication for Radical thinkers. Soon she was mixing with leading intellectuals such as Tom Paine, artist Henry Fuseli, William Godwin and many more. She regularly attended Joseph Johnson’s evening meals, steadily developing as a conversationalist and philosopher. Wollstonecraft thrived in this environment. She read avidly, translated books, learned German to extend her reviewing skills and contributed reviews regularly to the Analytical Review. She pushed her own development. She dedicated the second edition of Vindication of the Rights of Women to Talleyrand, a minister in the French revolutionary government, rebuking him for his proposal for national education in 1791, that relegated women to domestic duties. When he visited her, she served him wine in a chipped cup, so little heed did she pay to conventional manners. She was the same about her personal appearance until her attraction to artist Henry Fuseli caused her to smarten herself up.

How many of us women have been there? Resisting the pressures to abide by conventions in dress and gender stereotyping only to give way to ‘be attractive’? Wollstonecraft was no different. Caught in that contradiction – wanting to be taken seriously as a thinker and writer, or just seriously as a human being, and not the eternal sex object. But in the 1790s, how do you find a husband who will both love you and treat you as an equal? For Wollstonecraft was not against the role of wife in the family as bearer of children and their primary educator, provided this was seen as an equal role to that of the breadwinner husband and provided women were educated to the same level as men, with equal rights. The idea of ‘socialising’ the drudgery of being a wife, and women gaining independence through earning a wage, was born a few decades later in the mid 19th century.

Wollstonecraft’s life as a single woman was rewarding intellectually and she was much admired. However, despite support from Johnson, she remained poor as her money went on supporting her father and siblings. She felt the gap between public standing and failure to satisfy her personal and sexual needs most keenly. The first man she was attracted to as her equal, artist Henry Fuseli, was already married. She strove for openness in her relationships with people, often erring more on the side of candour than tact. She was a beacon of integrity, no false manners here. However, her life was wracked with physical ailments and mental anguish, perhaps the result of the contradictions between her public, personal and private needs. Her first experience of sexual love was to sharpen these contradictions.

Revolutions exercise a strong pull on those who want to see change. I went with several like-minded people to Lisbon in 1975 – to experience for myself the flowering of the Portuguese revolution with the overthrow of fascism. Mary Wollstonecraft experienced the same kind pull to visit France. She finally arrived in Paris in early 1793 where she mingled with the then leaders of the National Convention, the Girondins, as well as the emigre community. So she was there for the increasing violence, the transition from the Girondins to the Jacobins led by Robespierre and the war between France, England and the Netherlands. In the atmosphere of revolutionary upheaval where conventions about relationships were being challenged, she met the American Imlay. They became lovers in the spring of 1793, and she took his name to avoid imprisonment or expulsion from France. She soon became pregnant, giving birth to her daughter Fanny in May 1794 in Le Havre.

The relationship with Imlay was not to be her hoped for experience of two people, equal in love, passion, intellect and commitment. He was a failed man of commerce. Who hasn’t experienced the searing disappointment with a man who just doesn’t match their aspirations? I certainly have. But far fewer have left a record in personal letters of the love and pain, the swinging between hope that things would turn out all right, to outright despair that the relationship was finished. To those who decry Wollstonecraft for not living up to her own ideals of reason prevailing over emotion, I would ask, ‘haven’t you been there?’. Furthermore, Wollstonecraft’s aspirations for different kinds of relations between men and women were always predicated on men and women becoming different by growing up and being educated in a society governed by reason not by the cant of the gentry or the corruption of commerce.

Wollstonecraft was indeed buffeted by her affair with Imlay, but this did not stop her from writing a fascinating analysis, published in August 1794, of the first year of the revolution.

1789 was not marked in this by the violence of the Terror that followed, so there is no analysis of the impact of the developing civil war and the forces backed by England and the Netherlands to reinstate the monarchy. But although there is no doubting she loathed Robespierre, Wollstonecraft understood that explosions of rage were rooted in the violent repression of those who, until then, ruled with impunity. Poverty is another form of violence.

Wollstonecraft was fearless. She undertook a journey by sea during a war, with her one-year-old daughter and maid, travelling for three months in 1795 through Denmark, Sweden and Norway. She wrote brilliant letters throughout her travels, analysing the different ways of life, describing the scenery of the places she visited, providing vignettes of the people she encountered, often revelling in the sheer physical pleasures of walking, wild swimming, riding, sleeping under the stars; a physical appreciation of nature that has been rediscovered by many today. These published letters won the admiration of the Romantic poets and William Godwin.

Wollstonecraft abhorred the hypocrisy of her age. She dared to become an independent woman, a public intellectual who defended the French Revolution and argued for the Rights of Women, to become an unmarried mother and not hide her daughter away. Her voice was all but silenced as political reaction set in, following her death in childbirth in 1797 and the scandal caused by publication of her Memoirs by William Godwin. She was a kindred spirit in so many ways over two hundred years ago, but so much more courageous than I think I have ever been and a true inspiration to live by your beliefs.

Sheila McGregor – December 2022.

Great account of a full life – inner and outer – of a great woman. To manage political action and emotional vulnerability AND change the world…..wow.

I don’t like the statue though