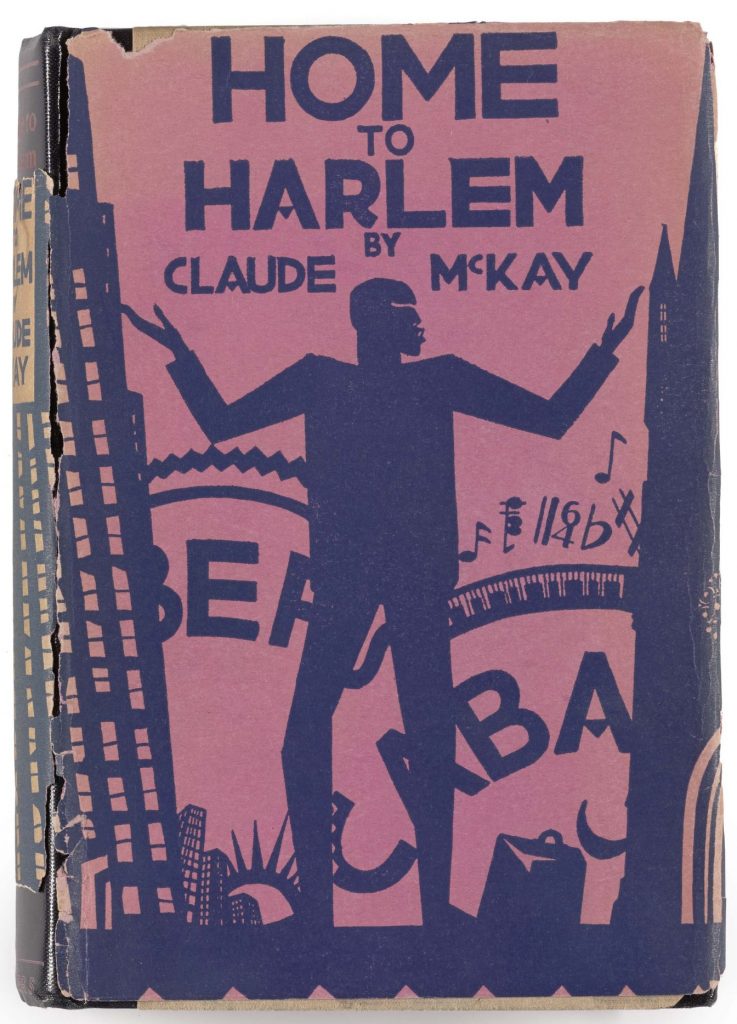

I knew about Claude McKay because for several years I taught a university class on African-American culture, and “Home to Harlem” – his best-selling. Novel of 1928 – was an essential text.

But the process of coming to know Claude has taken other routes.

A casual question asked to a then-84 year-old man in 1984, “oh, did you know Claude McKay?”. Which generated an emphatic answer: “know him?, know him? I was his office boy at “The Liberator” magazine in 1920.” That man was Carl Cowl, and he became in the 1940s Claude McKay’s agent and executor. For many years Carl was a lone voice in championing Claude’s writing and reputation. It is one of the great pleasures of my life that for fifteen years Carl was my good friend, an exquisite raconteur until the very end in 1997.

An exchange, the beginnings of which are now unclear, with the ‘Collectif Claude McKay’ – a group of people in Marseille – has led to:

the renaming of a street in that city where Claude lived and wrote;

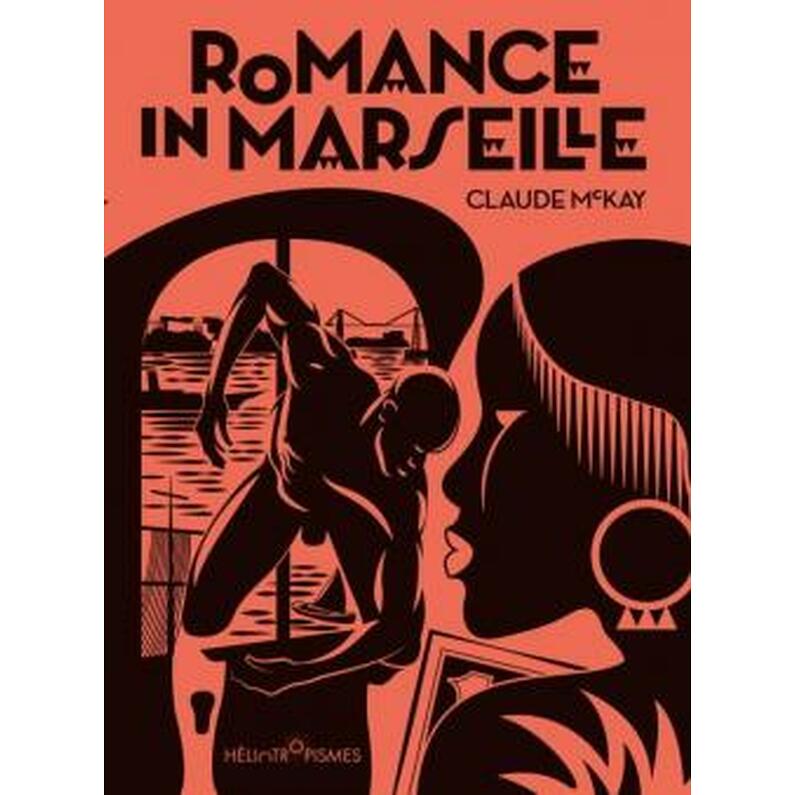

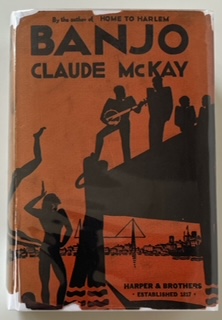

a glorious re-translating of his writings complete with beautiful covers that evoke Aaron Douglas’s originals;

and a series of international gatherings organised by the ‘Banjo Society’ based at the University of Aix-Marseille to celebrate and commemorate Claude’s life and work.

My failed attempt to guide an unpublished and disregarded novel into print. “Romance in Marseille” was seen in the end by the English academic publisher as just ‘too much’. By which I think they meant its socialist and pan-African politics, and its rumbustious depiction of sexuality in the Vieux Port. Twenty years later, when it was guided into print by academics with more influence than myself, it was hailed by “The New York Times” as “the most significant novel of 2020” – only ninety years after its writing.

Because there is, it seems to me, a difference between ‘knowing about’ and ‘knowing’. It is the difference between reading a novel once or, perhaps, twice as part of a course in which one reads other novels once or, perhaps, twice. And feeling the presence of a long-dead, much-neglected and even more-maligned, presence with an intensity that drives you to argue for years with a city council that they honour this exile’s presence as part of the city’s history and present life.

First of all, Claude wasn’t African-American. My first lesson. He was born and educated in Jamaica, then moved to the USA where the storm of racism that was the 1919 pogroms drove him to write the magnificently enraged poem, “If we must die”. My second lesson was that, in reading and re-reading and then re-reading again and again, I began to hear a voice that placed its anger alongside a formal subtlety that argued with and against English poetic tradition.

His subsequent European travels – from London to Moscow, Berlin, Paris and then to Marseille – were the bridge over which he moved from journalist-activist to novelist. His ability to make the ‘wrong’ sort of friends and comrades led him to work for Sylvia Pankhurst as a journalist on the “Worker’s Dreadnought”, and then to accept Leon Trotsky’s commission to write a pamphlet/book on “The Negroes in America” – a book now all but entirely lost beneath a heavy cover of Stalinist censorship.

In Marseille, with periods living and writing in North Africa, he wrote three novels. “Home to Harlem”: an account of working class Black life in the gig economy of post-WW1 New York. “Banjo”: a roaring plunge into the diaspora of the Marseille Vieux Port. “Romance in Marseille”: politely called a ‘picaresque’ work, it celebrates life of every sort and now reads as a direct contribution to our contemporary debates about diversity.

The first two were critical and commercial triumphs. The third was rejected by his publisher. Not long after he returned to the USA to a life of penury and ultimately fatal disease.

And, for many years, sank out of sight beyond a very small circle of supporters and friends. Those who did stand close beside him, remained very close.

Accident and coincidence brought me to his writing, and that has given me a very small place among those who have more than a simple academic interest in his work. The core of those people are the Collectif Claude McKay, based in Marseille and the Banjo Society, and I was more than delighted when I was offered membership of both groups.

What does Claude mean to me? An understanding that rage about injustice can exist alongside raucous celebration of friendship, comradeship and simple joy without being diminished. The slow recognition that his polemical fictions are also aesthetically sophisticated and have a claim to stand alongside the more obvious ‘great’ novels of the 1920s and early 1930s.

At the end of my first visit to Marseille, to celebrate Claude’s life and work, a man born in Somerset, as obviously ‘English’ as it is possible to be, was embraced by a man born in Angola, who grew up in Brazil and drifted to France. Our shared engagement with Claude was summed up by the latter’s words in that embrace. “Not ‘mon ami’, ‘mon frere.” Behind, within, alongside those words was a shared belief that Claude McKay’s writing rests on a bedrock of belief that all the imposed differences of geography, race, class,and – yes – even language can be overcome.

As a continuation of this article I will write some short essays about specific works by Claude McKay starting with the most famous of his poems, “If we must die”.