I really enjoyed “Maestro” while I was watching it, and then within a few minutes was infuriated with myself for having liked it.

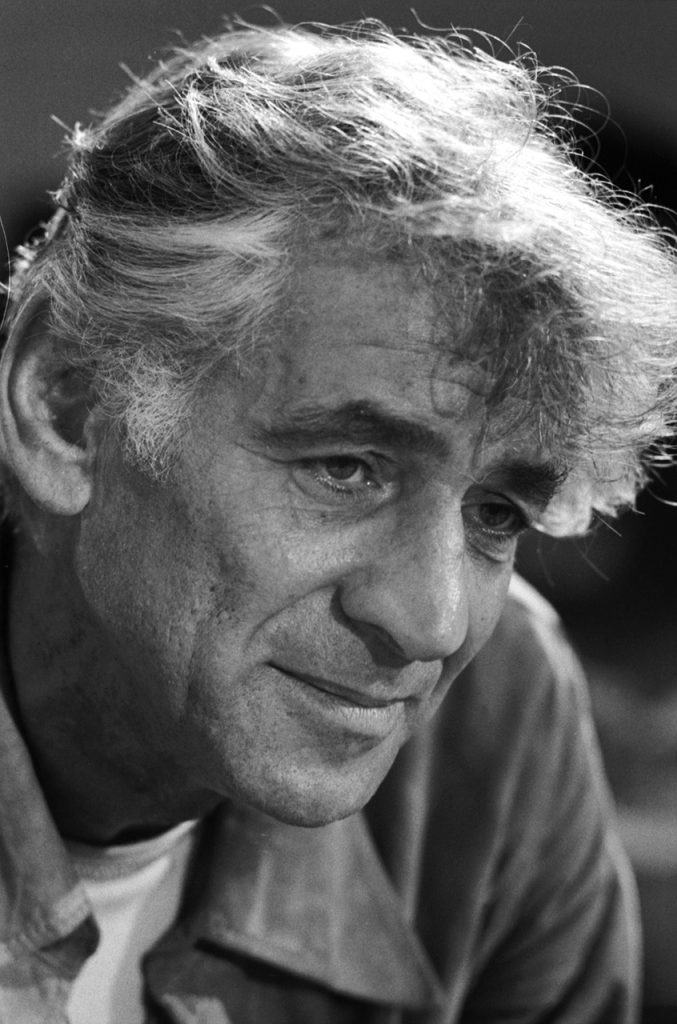

It is a thoroughly engaging film, interweaving elements of Leonard Bernstein’s professional life with his marriage, his children, and his affairs. A sequence in which Bradley Cooper as Bernstein slides from composing the music for “On the Town” to performing in one of the dances works well. The camera frees itself from what is most of the time a static position and whirls into the scene. It is an effective metaphor for, and an account of, an artist’s involvement with a work they are making.

On the whole “Maestro” follows a chronological path from Bernstein’s first lucky break as a conductor, when Bruno Walter (the great German conductor and in some ways mentor to Bernstein) is indisposed and he steps in at short notice and with spectacular success. From there to other conducting appointments, through the ‘controversy’ of a classical composer and conductor writing popular works, through the vicissitudes of his marriage and infidelities with other men, to the triumph of the “Mass”.

Why, then, the infuriation?

Much of the time I am wearied by reviews that tell me what a work didn’t do. James Joyce not discussing the impact of the Easter Rising in “Ulysses” – a novel set 12 years before the Rising – is one of the more absurd I have encountered. Yet I am about to do precisely that.

Because sometimes when a work doesn’t do something that – and I’ll argue the case – it should, this needs explanation. Especially when that work is, or claims to be, in some way biographical. Because by not doing something in favour of doing other things, a work can become distortion.

I’m aware of the immediate riposte that Bradley Cooper has the right to make whatever film he chooses, and I’ll come back to this assertion once I’ve outlined my objections.

To start. I’ll begin with a small quibble. The replacement for Bruno Walter is presented as a sudden leap and I appreciate the dramatic need for this. “A star is born”, one might say. But this means that an earlier production organised by Bernstein disappears. “The cradle will rock”, a revival of which he produced in 1939, is a ‘play in music’ about trade union organising. Written by Marc Blizstein, produced by John Houseman, and directed by Orson Welles, the original production caused controversies when it was initially shut down by the federal agency funding it and then independently produced by Welles and Houseman’s Mercury Theatre.

A small and indeed even, some might object, obscure quibble. But it speaks of a larger problem. And that is the elimination at every stage of any sense of political involvement.

That becomes ever-more obvious as the film continues into the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. There is no mention of Bernstein’s involvement in support of the civil rights movement, his protests against the Vietnam War, his campaigning for nuclear disarmament. In the 1980s he was raising money for HIV/AIDS research and awareness.

There is also absolutely no mention of the incident that provoked the unpleasant and snotty article by Tom Wolfe (then an influential journalist and essayist, who went on to write “The bonfire of the vanities”) entitled “Radical Chic: that party at Lenny’s”. This mocked Bernstein’s organisation of a fund-raising event for the families of the imprisoned members of the Black Panther Party. Given the subsequent popularity of that stupid phrase, this is a particularly revealing omission.

Even more unforgivably, perhaps, is the erasure of the political activities and campaigning of Bernstein’s wife, Felicia María Cohn Montealegre. As well as a long involvement with prison reform campaigns, one such alongside Coretta Scott King (the widow of Martin Luther King), she was also active supporting the refugees and people imprisoned in the aftermath of the military coup and subsequent massacres in Chile in 1973. A sharp response from her to Tom Wolfe followed the previously mentioned article: she said, “The frivolous way in which it was reported as a ‘fashionable’ event is … offensive to all people who are committed to humanitarian principles of justice”.

Particularly egregious, perhaps, because under Bradley Cooper’s direction Carey Mulligan’s performance is as a cipher and victim of Bernstein’s trajectory through the years of his life and work.

Enough of the politics, I hear you cry, what about the music?

Well. Yes, indeed, what about the music? Here again, there is a bizarre decision to remove “West Side Story” from the, um, story beyond a one-sentence reference. That’s it for a musical that disturbed 1950s USA with its suggestions of cross-ethnic romance and working class youth’s vibrance and creativity. When finally we do get to a sustained engagement with a piece of music – that is, an engagement that goes beyond a few bars accompanying Cooper waving his hands in the air – it is an extended scene reconstructing a performance of the glorious “Mass”. Any indication of its occasion, its place in American classical music? You guess.

Again, though, I hear the response that all these exclusions are a directorial, a production, decision. Well, yes. And in many other cases I’d accept that argument. Except that this claims, in some way, to be a biopic. A biography on film. So deliberate exclusions matter in this case. After all, Kirk Douglas managed eventually to wave a paintbrush in “Lust for life”, even if every other element of that film parodied Van Gogh’s life.

This needs placing into a wider context. In which, first of all, the political activities and opinions of anyone not a ‘professional politician’ are marginalised, mocked or denigrated. The storm directed at Gary Lineker for his marvellously unrepentant messages is partly because the content, partly because (ex-)footballers should be incapable of any informed activity above their shins.

It’s also a little more specific. There’s a long-running and now-revived narrative about the awfulness of the 1970s and that, it seems to me, is about an attack on the very idea of resistance. At a time when, now more than ever, resistance to the hurtling rush towards awfulness in all its guises is a necessity, abusing or even more insidiously denying the existence of the possibility of resistance is “offensive to all people who are committed to humanitarian principles of justice”.

Why does this matter? Well, cinema is a global industry, with global influence. One Indian reviewer pointed out that this film will probably be the first encounter with Bernstein, his life and work, for many Indian viewers. When Indian cinemas command such vast audiences that makes the failure of this film even more serious. They are left with a parody rather than a portrait of the complete man and woman.

I agree. The movie felt heavily edited. I had no idea who some of the supporting actors were. The solution should have been obvious. Bernstein deserved a mini series like the terrific Fosse/Verdon miniseries. Sadly I lost interest about 75% of the time. There was a recent poll in one of the American media outlets which ranked Maestro ten out of ten for enjoyment of the ten films nominated for best picture at the Oscars.

Thanks Ernie. Lovely to hear from you! The poll is interesting. I enjoyed the film (but I do also think film should be about more than just enjoyment!)

Good piece Richard. I did know anything of Bernstein’s political life until just after watching the film. The performances are very fine, as is the chatter on making great music. The troubled arts and all that. But to omit their politics? Nah. Oh – and it was – I hear – partly funded by the tobacco industry.

Thanks Jan. There’s a good deal of political avoidance in movies, now certainly but also in the past. I wouldn’t want to argue that all movies should wear an easily-seen political badge but when the subject-matter stands close to politics it seems deliberate to avoid it.