It is tempting to wish to divide literary production along binary lines. Ben Jonson’s constipated complaint against Shakespeare’s easy, diarrheic even, flow preceded the tightened distrust of conservative critics when confronted by Kerouac’s great rush.

I have another of these seemingly grand, probably deceiving, divisions in mind that proceeds not from the bowels but from geology. That sees Kerouac, D H Lawrence’s ‘first thought, best thought’, as the volcanic eruption of prose. A Hartland Point mode that twists and buckles the flat lines into sweeping curves and contortions that sometimes supplant careful meaning with bravura rushes of upswelling language.

And the other process is, of course, sedimentation. The settling of sands and clays onto a substrate. The steady, cumulative addition of words, phrases, ideas that over time turn from seabeds into mountains and cliffs. This is the Jurassic Coast mode of writing.

In recent years, the shift in the tools of composition from hard copy of various sorts to screen is steadily depriving future scholars and academics of the evidence of the processes by which texts get made. The anxiety that this has induced has a reflex in the development of what is called genetic criticism. A way of reading texts which is rooted in examining drafts and early versions, so as to see the development rather than the finish. The process rather than the product.

When James Joyce was persuaded that publishing Ulysses might be a possibility rather than a thwarted wish, his typescript was delivered by Sylvia Beach to a small traditional printer where the text was typeset by hand and proofs were printed. Which were duly delivered to Joyce for approval, only to be returned with corrections (many went ignored or missed) and – more importantly for my present purposes – additions. A process repeated several times. To the point where the typesetters – setting the text by hand and necessarily backwards and in another language – began to leave spaces in the forms of each page so that they could add Joyce’s later thoughts without the tedium of having to re-set and re-paginate later pages.

One estimate is that, in this less-than commodious recirculating, the novel grew by up to a third. Even, so the anecdote goes, that when the final proofs were finally ready to be printed for the book to be ready for Joyce’s birthday, a telegram was sent late to the printers with just one more word to be inserted.

We can, I think, be fairly sure that Joyce was not making significant additions to the plot. [See my footnote below for a tale of plots and sub-plots]. That arrived early and is of almost secondary importance to the novel – it is a tale swiftly told. What he was doing, it seems to me, was adding the sands and clays of language and thought to build the monumental cliffs that are this book.

The implications for us as readers are obvious. If we read this novel for plot alone we will be disappointed, but we will have prepared a foundation for subsequent readings. We know what happens, and now we can re-read for how what happens, happens. And that ‘how’ is itself made up of many layers. Or many threads. Any single metaphor for reading will be insufficient. Let me explore these two a little further.

With the narrative in place, the most obvious addition is the parallels to the Odyssey. And, as I’ve argued elsewhere, I see these as more imaginative and speculative than schematic. There are few simple one-to-one connections but rather the moment of contact acts as a spur to the writing. So, “Calypso” refers us to the story of Odysseus’s sexual imprisonment and that acts as an ironic contrast to the account of Bloom’s now-asexual relationship with Molly, which in turn is set alongside her very definitely sexual relationship with Boylan and Bloom’s response to the presence of that relationship in the bedroom of his home. It is no accident that he and Molly sleep head to toe.

Next comes Joyce’s bravura stylistic performances, which render the book as an account of the modes of writing in (English/Anglo) literature. “Calypso” again. Joyce’s deliberately deliberate rendering of early twentieth-century English literary prose – think, Arnold Bennet or John Galsworthy – is almost agonisingly close to these examples. And then drags their supposed commitment to social realism into a jakes. “This, too, is life”, Joyce seems to say both through content and mode of writing.

Thereafter, the layers accumulate and their accumulation has both kept the Joyce Industry’s wheels turning for many years and has, I suspect, greatly pleased him in Zurich graveyard exile.

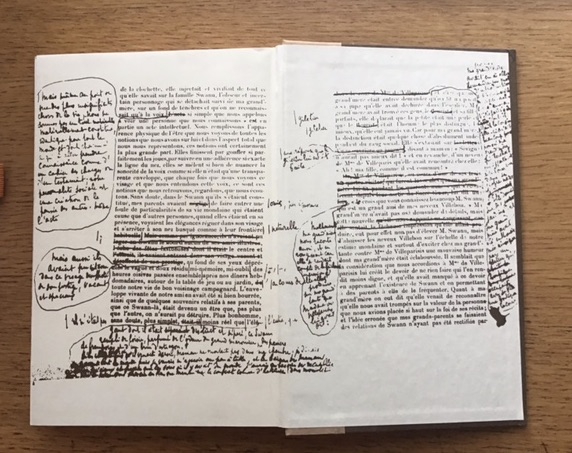

He was not, and is not, alone in the sedimentary process of composition. As a gentle preface to another of my ambitions, I offer you a page from Proust’s proof corrections and additions for “Swann’s Way”.

The Footnote.

A novelist friend, as his career waned, rushed a short novel into existence. To be told by his editor that it was indeed too short and needed a sub-plot bolting in. Suitably enlarged by a writer skilled in the art of fast writing, the book now proceeded through the hands of said editor and off to the printers. Where worked an avid late-night reader of books-to-be. Who wrote to the editor and the author, pointing out that a character killed in the bolted-on sub-plot seemed to have been miraculously and without explanation resurrected later in the novel. Cue, rapid corrections.

Thanks to Julia Joppien (@shots_of_aspartame) for the image.

We have just one page of Shakespeare’s handwritten script surviving the 4 centuries between him and us. However, drama is different: because, like music, it lives in performance (scripts are like musical scores) we can track evidence of Shakespeare’s plays evolving through theatrical artefacts. Differences between the cheap, single-play editions (quartos, sold when a play had just left the stage) and the first collection of his work (the First Folio, put together 7 years after his death) reveal plays being recast or recut for different spaces more often than you’d think. A big, open air stage means no need for act breaks, more room for fights, slapstick and dances, but an indoor space is good for subtle sound, psychological tension and light effects. Differences between quarto and folio editions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream are a good example of this.

Most clearly, there are two distinct versions of King Lear (the ‘History of’ and the ‘Tragedy of’) with differences amounting to over 100 lines. Modern editions conflate favourite bits from the two, as they do with the various versions of Hamlet, but they are distinct texts – one a re-working of the other. The politics in King Lear could also have had something to do with that rewriting – it was played on the 26th December at King James I’s Christmas celebrations and speaks powerfully about destitution and outsider status to that lavish court.

And that surviving handwritten page of Shakespeare’s script? It comes from Thomas More, a play by another writer that he, then a young playwright, worked on with colleagues to improve and make stageable. Drama back then was regarded as mobile, reacting to spaces, times and places – disposable, even. Shakespeare may have hoped that his lyric poetry would give him immortality but he never expected the plays to last – plays are not fixed by pages.

Thanks for this, Maria. I regularly use that speech from “Thomas More” in other contexts! And I found your comments fascinating, and another really useful and revealing version of the mutability of the text. Would you be prepared/happy to turn one of your examples into a more detailed account? I’d be really interested!!

Glory to the anecdotal? typesetters who “got” Joyce’s propensity to sediment and agreed to accommodate it with a generous page or two or three. But then the evidence is lost to us too except through story, process absorbed into product.

How much livelier the marginalia of Swann’s Way, I will say, a cartoonish conversation in a cramped space. There’s Proust, in the guise of a (dissatisfied) re-reader, talking over his own printed word, a visible dialogue. And, I gather by his selfsame hand.

With all due respect just as well sedimentation is subject to erosion or one is left with ozymandian arrogance, like 920 plus boxes of paper everythings, courtesy of Norman Mailer. Lots of these were typed by his secretaries, and evidence of their sedimentation–interventions? is buried in those boxes. Whether this evidence is worth the storage is a question of literary time.

Thanks Eva. I really like the tale of the typesetters first-guessing Joyce with their blank spaces.

And Proust, the pandemical patron saint, second-guessing himself. I’m going to reread the later volumes, to try and see if his premature pre-publication departure has a discernible impact.

As for Norman, well I for one can only hope that the power of erosion grinds down the mountain.

Archives are evidence of something – or a heap of different somethings maybe. It is up to the later scholar, reader, enthusiast to work with them as they can. That is also their particular, intimate joy: an unguarded glimpse of the distant literary figure, a sliver of corroborating evidence for or against a theory, maybe even a new idea that reforms an old prejudice, sitting right there in among the dust and detritus of his or her life.

The further and stranger we are from a writer’s work, the more helpful an archive becomes. I posted my bit about Shakespeare (13th November, above) after being in a Zoom meeting about the archive of a great director and scholar, John Barton. He left the contents of a flat to the Royal Shakespeare Company, and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust is still sifting the 100+ boxes of papers and workshop recordings. His death is recent, so people who worked with him as he and Cicely Berry changed radically the style and clarity of the RSC’s approach are still alive to add their insights, adding to our overall understanding and interpretation. But what about the authors of the ancient scripts he was directing?

Visiting the Dulwich College archive this time last year, I was thrilled to dig into a much smaller volume of material than the John Barton archive contains. Dulwich is where the big chest stuffed with the papers of entrepreneur Philip Henslowe and star actor Ned Alleyn, Shakespeare’s rivals at the Rose Theatre, is held. Now 400 years have passed, all surviving evidence is precious, not to say fundamental. Without Henslowe’s account books documenting his company the Admiral’s Men, their props, payments, repertoire, even his flyleaf doodles and the various spellings of his own signature as he tried out a new quill, there is so much modern historians, writers and practitioners would not know. They were the practical, everyday book-keeping of an organised man who never wrote a play. But we could not have reconstructed Shakespeare’s Globe without them.

Maria. A solid reminder that the text, the play and its performance, certainly the movie, we receive is never from one hand. [And whisper it quietly, but there are a number of authors whose stature outlived and outlives the hand of a good editor].

So thanks again – It’s a real pleasure to have a Shakespeare scholar on board!