by guest blogger, Cally Hayes

RACHEL When it’s really bad it feels like my blood is on fire

I can feel it in my veins

all through my veins it feels like burning

I can’t it’s almost like my body can’t turn off

like someone’s turned the switch in my brain and it won’t go off

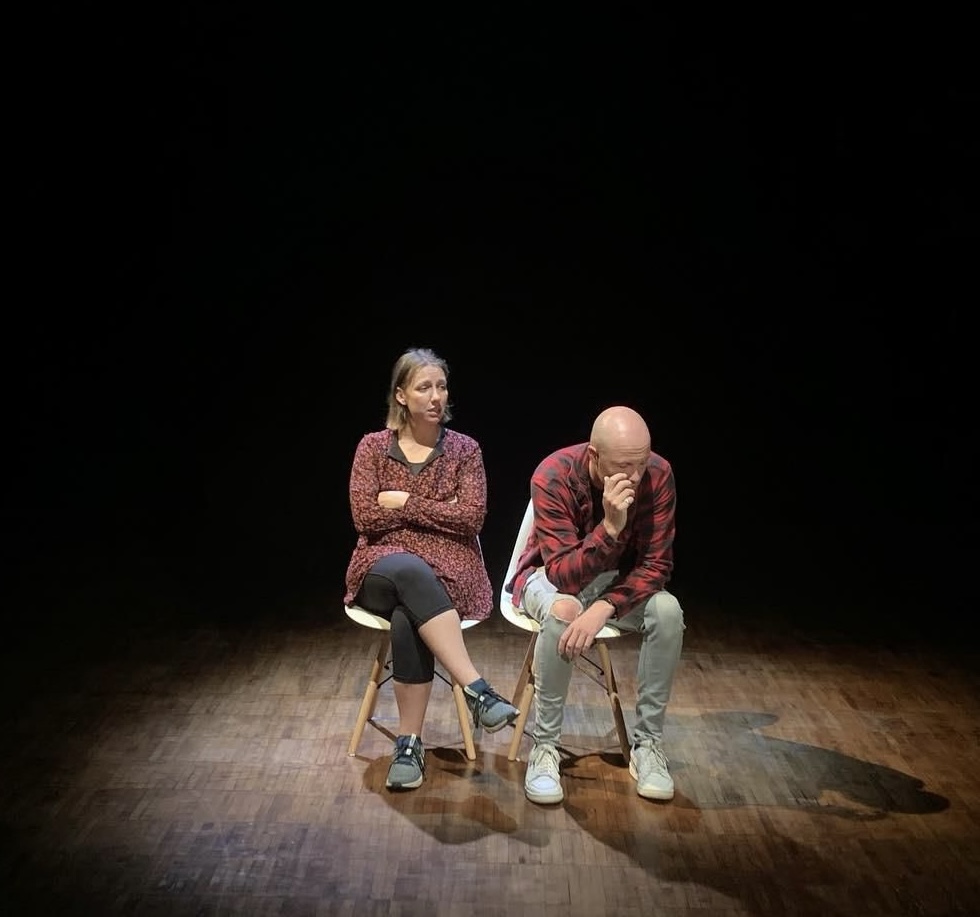

Cracking 2019

As I sat listening to Amelie tell me her story of postnatal depression, it was like a switch in my brain had been turned on. Her description of her experience was so visceral that my brain was exploding with ideas about how this could be translated onto the stage. And so began my love affair with verbatim theatre.

For many years I had worked in the NHS as a community mental health nurse during which time many stories had been shared with me. When in 2014, I was asked to create a short piece of theatre for a regional perinatal mental health conference, I grabbed the opportunity.

By this time, it was not unusual for ‘experts by experience’ to speak at conferences but retrospective story telling was not without its problems, least of all in the way that it connects with the audience. Creating a piece of drama would allow audiences to enter into the world of the characters, right into the eye of the storm to experience what the characters are feeling without ‘experts by experience’ having to relive it all, whilst allowing a range of voices to be heard and represented in a vividly immediate and memorable way.

And so I met Amelie and her husband and several other couples who agreed to be interviewed. What was immediately apparent, was the information available to me as a writer in terms of the emotional context beneath the words. The rhythms and pattern of speech, the interruptions, the non verbal exchanges between couples and what is left unsaid. All of this lent itself to finding the theatricality and the characters but what really interested me was how the rhythms and patterns of speech also lent themselves to externalising the repetitive nature of ruminating thoughts and cycles of depressive thinking. There is almost something musical in these idiosyncratic rhythms and once in the rehearsal room, I was able to explore with the creative team how these could be translated into other theatrical languages of sound and choreography. It was clear that these were going to be key tools to express the play’s emotional intensity.

Working as an ensemble, we listened to the interviews and explored through improvisation, the characters and plot, selecting and arranging excerpts to create a compelling structure. Our characters were an amalgamation of more than one person.

The biggest challenge when working with personal testimony, is how far you can stretch the source material to reflect unlikable character traits at moments of stress to create dramatic tension. We spoke to a number of men who had supported their partners through severe postnatal mental illness, who shared behaviours they were not proud of when caught up in the eye of the storm. From the outset we enter into a contract with contributors that gives them complete editorial control but it is much more than that. As a creative team, we are building a relationship with our contributors that puts them at the centre of the work. I spend time explaining the aims of the project, the creative process, their roles within it and the impact we want to make before any interviewing takes place.

I choose to interview contributors in their own homes so I am in their personal space. I think this is important in conveying where the power lies in this creative collaboration.

Central to this process, is respect for the stories they are sharing with us and a collaborative approach that creates opportunities for contributors to get involved in creative decisions about the performance. As a writer and collaborator, I am open to all ideas in shaping the story and if I’m not sure about something or feel an idea is moving away from my creative vision, I still want to fully explore how it serves the story. The key is being able to communicate the vision and to sit with the discomfort in the chaos of making a play before the creative decisions start to get nailed down. It’s not something as a writer that I’m fully comfortable with but I try to embrace it because you never know what wonderful things you will find.

Not everybody wants to get fully involved in the creative process but for those who do, we provided a workshop to explore themes of the play and key messaging with a shared lunch. Doing it in the summer added the bonus of hanging out in the sun to eat together. What I have learnt from doing this work, is the importance of taking care of everyone in the creative process when you are dealing with emotionally charged and difficult content.

This coming together is hugely beneficial for the actors in terms of finding the authenticity in their performance but also gives them permission not to hold back from some of the darker aspects of the story we were trying to tell.

All contributors received a script of the finished piece and the opportunity to attend an open rehearsal so that we can have feedback and any changes to the script can be made before the opening performance.

I always tell contributors that the editorial control remains with them until the show opens.If anyone wants me to delete something from the script, even if I think it’s a killer line, I will do it out of respect for their lived experience. So far, this has not happened and I think it’s because we have designed the creative process to bring contributors with us so they feel invested in the project and there are no hidden surprises or conflicts of interest.

What has struck me in working this way, is the importance of the relationships made with the creative team and the collaborators and the impact of that in enabling contributors to move forward with processing their own traumatic experience. During the interviewing, it was clear that I was being told things that these couples had already said before to each other but with every interview a new truth was revealed. Something that neither of them had spoken of before that proved to be helpful in their recovery journey. A profound example of this was when during one interview, a woman spoke of how she let out a wail like a wounded animal when at her most despairing. She turned to her husband and said, “I don’t know if you heard that?” And he quietly replied “Yeah I did.” Apart from a moment of pure dramatic tension, I was witnessing a moment of a new understanding between them. Needless to say those lines ended up in the play.

As one couple said, being involved in making the play was cheaper than therapy!

I wanted to write a play where the audience fall in love with the characters, where they feel like people you might know and that comes out of the source material and the relationships forged during the creative process.

For me, verbatim theatre reveals the extraordinary in the everyday, celebrates human resilience, and harnesses the power of art to engage with vital issues—challenging us to imagine a more compassionate world. And that’s what I love about it.

This is very very interesting and reminds us of that vast part if the iceberg of creativity (not a great analogy as ice is cold) that remains hidden. The audience of course enjoy the fruits of all this – often not realising the amount of committed work needed to bring a production with emotional truth and depth to the stage or screen. Work with this truth and knowledge stands out. Bravo